Comparing countries in the corona virus? Call an expert!

Apr 29, 2020 · by Richard Farkas

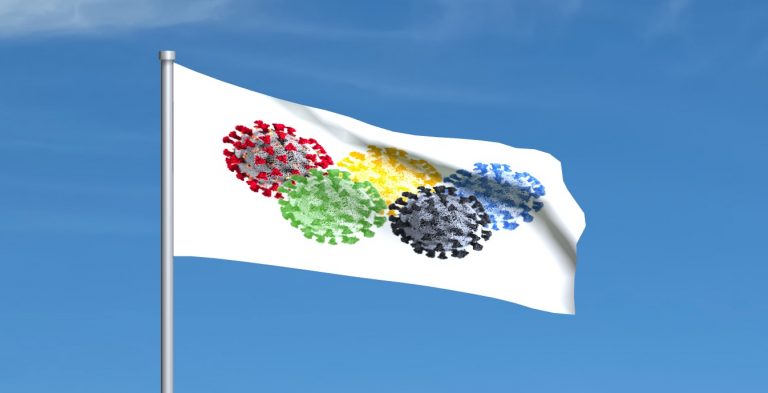

The coronavirus stole our 2020 Olympics, but the disease has given us a new way for countries to compete. Journalists are enjoying Olympic-level interest in their articles and video reports as countries battle to rank first for Personal Protective Equipment, to achieve a world-record for pop-up hospital construction or to win the race for contract-tracing apps.

News reports also give us the Covid-19 sporting tragedies, as new countries suffer a humiliating collapse in hospital bed vacancies or care-home survivals. Policy-makers also look to other countries as a measure of how well they are meeting the Covid-1 challenge.

International comparison: a new Olympic sport

The intercultural profession offers valuable expertise here. This is a community of researchers, trainers and consultants specialised in the successful adaptation of people ideas from other cultural contexts and the forming of global solutions in local circumstances.

With nothing to report in the newspapers’ sports-reporting sections, the new sport of international comparison has emerged to fill newspaper columns.

Comparing Country A with Country B sounds simple, and learning from other countries sounds like the obvious thing to do. But what if we are misunderstanding the experience of other countries and taking the wrong lessons from those international comparisons?

International rankings are filling a gap in the science

We have 150 years of epidemiological science and decades of research into the socio-economic determinants of health, but we yet don’t have the peer-reviewed science of Covid-19. With the new science lacking, and traditional epidemiology too mathematical and complicated, simplistic conclusions from international comparison are having a disproportionate impact on political decisions.

Simplistic conclusions from international comparison are having a disproportionate impact on political decisions

Presidents, Mayors, Prime Ministers and Secretary Generals come under pressure to show leadership and “do something” or be more like South Korea, “Do what the Chinese did”, take the example of New Zealand, or follow the Germans.

Effective leaders think interculturally when facing global challenges

What are these comparisons presented to us so confidently by journalists and repeated by politicians? While the smart policy-makers and business leaders these days use sophisticated intercultural models for rolling out global programmes with local sensitivity, this is rare among the media and politicians under pressure.

Mark Twain famously warned that comparison is the death of joy, but there is great advantage to international comparison, done well.

We need to approach international comparison with humility and caution. What principles would inform an international comparison, given the benefit of coaching from interculturalist?

An interculturalist in the coronvirus response team

Apr 14, 2020 · by Richard Farkas

What contribution might an interculturalist bring to a top coronavirus crisis response team? Some of the best-prepared government bodies, NGOs and businesses have been adapting to the new situation equipped with cultural intelligence developed by intercultural professionals.

Here are ten things to keep in mind when comparing countries in the coronavirus crisis.

Do the maths

Adjust for population and other relevant variables

Comparing absolute numbers gives us a severely distorted view of what is happening. The absolute death figures and other grim national “milestones” are irresistible to some journalists, but we need to look at more variables than just “country”.

The UK’s death toll rose to 233 on Saturday with a total of 5,018 confirmed cases. This is the exact same number of fatalities experienced by Italy two weeks ago

Daily Mail, March 22nd2020

Deaths per million offers a less distorted view. So now we’re adjusting for population. we’ve made a multi-variate analysis. Let’s continue down this route. In this epidemic, when looking at national figures, it is useful to adjust for

- Urbanisation

- Population density of cities currently experiencing outbreaks

- Age profile of the population

- Incidence of multi-generational households,

- Representation of minority communities disproportionately affected by the disease

- Presence of transport connections and international transport hubs in the country

- Physical borders of islands and other geographical features

- The local season (hemisphere)

And so on. A multi-variate analysis gives a more useful comparison of the performance of nations tackling the disease.

It’s time to find your inner geodemographer. The least we can do is adjust the numbers for population and age.

Check the stats

Dig down to find what each number represents

Of all things in life which seem to have no grey areas, death seems to be the ultimate example. Counting deaths would seem to be an objective, inarguable exercise. But even here, we have to ask what does each country mean when it records a Covid-19 death?

We could also ask what do we mean by “tests”, “beds”, “deaths among frontline health workers”?

While France seems to be one of the worst-hit countries, its death figures include large categories – such as deaths in care homes – which are excluded in other countries’ death figures.

In many countries we know that official figures report what the authorities wish to report. The numbers reflect political decisions more than transparent reporting.

It is useful to consider how much trust the official figures traditionally earn among the country’s own residents, and how the country performs in rankings such as Transparency International’s corruption perception index.

We also need to look under the skin of the national figures. Is the data collected consistently or is there internal regional variation? Are there categories of inhabitant conveniently overlooked by the statistics or communities with wildly different outcomes, masked by average numbers?

Don’t get personal

Look at the whole country, not just the leader

The Secret to Germany’s COVID-19 Success: Angela Merkel Is a Scientist, wrote the The Atlantic on 20th April 2020. Political leaders are sometimes useful symbols of the way a country’s general population thinks and acts.

In this crisis, Emmanuel Macron is painted as the thinker, pondering the epidemic’s meaning for globalisation and Western society. Donald Trump as (at best) the electioneering liberator from overbearing public authorities. President Xi as the firm hand assuring stability of Chinese society, at all costs. Leo Varadkar as the caring doc, Jair Bolsonaro as the provocateur.

But as the disease sweeps through country after country, what is having far greater effect than the personality of the leader are the hard epidemiological realities of household size, geography, age profile, health system, access to clean water and long-established cultural practices.

Germans are no doubt benefitting from having a federal leader who is comfortable with numbers, but it is beyond the influence of one woman to have created a society that falls so naturally into the role of cautious, systematic, hygiene-conscious, law-abiding, mask-wearing expert distancers.

Beware the narcissism of small differences

Zoom out to see how things look on a global scale

Historian Elaine Doyle sparked a fiery debate recently on the comparison between the UK and Ireland.

Her Twitter thread and later article explored the different outcomes for the two countries in terms of deaths per million. This seemed to be fertile ground for comparison: two countries sharing the same islands and with much common cultural heritage. However, when we zoom out and think global, the differences shrink to a level which seems to fall within the range of sampling errors and phasing. Zooming out also gives the opportunity to compare with countries where there are other interesting comparisons: NZ, Japan, Finland, Australia.

Measure success against the goals in each case

Check what each country is trying to achieve

The standardised tables ranking countries in the corona virus crisis seem to put all countries into the same race, like a league table of football clubs all chasing the top spot or sprinters listing for qualification into the Olympic 100m final.

But in the coronavirus crisis and other national projects, different countries have different goals. While one country may be competing in the 100m sprint, another country is playing the relay race amongst its regions, or merely warming up for tomorrow’s marathon.

From population studies such as the World Values Survey, we know that values vary significantly between nations. And between governments, operational priorities vary. Public authorities manage within different constraints of health service resources, economic resilience, long-term thinking, short-term survival.

In the corona virus crisis, we see the very different ways that nations approach the uncomfortable task of putting value on human life as they experiment with various lockdown tightening and easing actions.

In Denmark, a country not afraid to run social experiments, we see policy-makers finding a “Danish balance” between maintaining democratic freedoms and risking higher levels of infections. The balance is different in countries where authorities place a higher value on certainty and security.

In Germany is it the same self-confidence and determination that helped them absorb the shock of reunification in 1990 and in the migrant crisis of 2015 which today gives them the belief that they can engineer themselves out of almost any problem and so beat the virus? The goal here is to win by well-coordinated technological and social action.

Meanwhile in Haiti, a country which has suffered recent epidemics of AIDS, cholera and TB, where clean water is a privilege enjoyed by the minority and crowded, insanitary living conditions are normal, should we be surprise to find fatalistic acceptance that the country’s weak health system will simply not cope? Here the goal is not to beat the virus but something more modest. NGOs and local organisations are aiming to increase access to water and soap for hand-washing. With workplaces re-opening even before the first wave of infections had passed, many Haitians expect to keep the rhythm of normality, which is the only way for most families to ensure that they can continue to put food on the table.

When we’re comparing performance in the corona competition, the fairest metric is how well each nation is achieving its own goals.

Don’t make countries into symbols of something

Allow some complexity and some internal contradictions into your understanding of each country

Countries differ, but they are complex and we must resist the temptation to caricature national cultures.

For the bloggers and journalists, Sweden has become the symbol of the carefree business-as-usual approach, Italy’s hospitals the symbol of crisis management, the USA the symbol of top-down chaos. Germany is given the role of supremely-confident Best-Prepared Western Country. China is painted as the victorious regime where the disease is beaten. New Zealand gets the role of quiet backwater which the virus never really reached. And Singapore is praised as the over-achieving Asian nation which administered the disease out of existence.

In each case the myth is false or hides a far more complex situation. In Germany, fear was a major motivator, as Die Welt put it “Politik der Angst”. In Sweden, everyday life has seen dramatic changes.

In the USA charismatic and competent leaders are shining at State, City and enterprise levels. In Singapore, the cracks in the country’s immaculate image are showing, in the desperate situation in the dormitories of low-wage workers and the emergence of a second wave of infection.

When a country is presented to you as a simple case of Category X or Category Y, there may be some truth or even hard evidence to support the story. But drill deeper and you’ll find plenty of confounding exceptions.

Look for contrasts

Find the surprising as well as the familiar

At times of uncertainty, we are drawn to the comfortable and familiar. No doubt with good intentions, journalists are falling into an easy trap of believing that people are the same everywhere you go.

Italy’s Coronavirus Response Is a Warning From the Future The Atlantic

Italy’s Nightmare Offers a Chilling Preview of What’s Coming Bloomberg

Headlines suggest that all countries inevitably follow the same path.

But when we look into another culture, sometimes the contrasts and surprises are more enlightening than the similarities.

Are the journalists succeeding exploring the immense cultural diversity apparent in the coronavirus crisis, and its implications for readers back home? Have readers been asked to put themselves into the shoes of a truly foreign person, perhaps like…

- the Seoul resident who receives a call from the police, because she have left the State-loaned tracking device untouched for two hours

- the Swede whose public health authorities say they cannot and will not try to stop the deaths completely

- the Brazilian or American who joins a crowd of politically-motivated protestors at a time of lockdown

- the elderly British person who refuses to visit a hospital where there are plenty of staff and space to care for them

Around Europe and the USA, commentators looked at the experience of Northern Italy and concluded that that would inevitably come to their country too. With the best intentions and a belief in our common humanity, they missed the fact that local conditions can vary so much.

In fact, the pandemic is turning out to be a series of very different local epidemics, playing out in contrasting ways in different locations. Finns and Bulgarians are finding out that there was nothing inevitable about following the Northern Italian experience in their countries.

A large part of foreign reporting in the corona crisis has been an exercise in finding a narrative in other countries which we want to promote in our own country.

By appreciating the deep differences between nations, we can make more sophisticated predictions about how global phenomena will manifest in different locations.

Know the communication styles

Interpret what people say according to the culture from where the speaker comes

Foreign correspondents of news organisations typically report with deep insight and empathy for their host nation. But the coronavirus crisis has given us journalism based on short-term assignments or even internet research where are articles are penned with very little understanding of the countries which are the subject of the article.

When a travelling journalist sent on a corona virus mission into an unfamiliar culture, or even a Zoom meeting, the signals can be misleading and confusing. Are those journalists equipped with cultural filters to interpret what their interviewees are saying?

While Iranians and Italians may talk of their corona virus experience with colourful, hyperbolic language, stoic Estonians, cautious Russians or fatalistic Indonesians may report similar experiences in very different ways.

Aside from words, actions also need a cultural lens.

Impressed by the strict rules and harsh punishments in Poland, journalists may wonder why in the Nordics the authorities offer mere “recommendations”. In fact, expert recommendations carry enormous weight in the Nordic region. The effect on behaviour of expert guidance in the apparently soft regimes of Northern Europe can have similar force as the “harsh punishments” of Asian countries.

The Polish and Nordic approaches seem to differ, but in each case the action is appropriate to the culture. These different methods may in fact be very close in their intention and effects.

Don’t declare victory 3km (2 miles) into the marathon

Give more attention to the direction, speed and the route and less to the current position

As the virus moves relentlessly through the global population, it arrives, accelerates and sometimes slows at different moments and different paces and different places. Live comparisons of the racers in this marathon are meaningless. Looking at how countries move along the Corona curve is more informative.

In fact, some countries specialise in a wait-and-see approach, seeking “last-mover advantage”. Luxembourg, for example, has a long pre-epidemic tradition of conservatively waiting to see the trials and failures of its bigger, trend-setting neighbours before deciding what to do, and then usually doing it better than any other country.

In some national cultures, political and factional debate seems like delay, but then implementation is swift and effective. In others, nothing much happens until the shit hits the fan, then resources are mobilised at impressive speed (yes, we are looking at you, US and UK).

International comparisons need to be adjusted for time and place. In the sporting world and in many Paralympic events, we give attention to personal bests. In the international coronavirus competition, a good measure of performance is how each country is faring in comparison to its own normal fluctuations in mortality or earlier crises. Instead of looking at who is leading the international rankings, a better question is in which country is achieving new “personal bests”?

The Netherlands was one of the first countries to draw attention to the variation on its own historical death rates, rather than looking across borders at how the neighbours are doing. The New York times used this as the basis for a more sophisticated comparison of self-comparisons.

Whether a fast-moving crisis or in slower, longer-term development, appreciating the phases of development is essential to evaluating the performance of different countries.

Stay friendly: you might need each other

Use comparisons to enlighten both sides

A storm blew through the 1984 Olympics when South African Zola Budd tripped American runner Mary Decker. It seemed to be a case of unsporting behaviour. Although spectators and media found the story fascinating, it meant we never got to see two great athletes complete the battle at full strength.

Who tripped whom?

In the coronavirus crisis of 2020 there have been some collisions on the race-track too. Personal protective equipment has been diverted en route from one country to another, leading to accusations of modern-day piracy. Travel has been unilaterally banned, and international comparisons have been used to brag against rivals.

The conversation around UK-Ireland comparison in death rates became so tense that inevitably the Twitter storm summoned shadows of past conflicts and historical injustice.

Similar barely-disguised antagonism exists in the comparison of China and Western countries’ handling of the virus.

Instead of following this dark, combative route, we have an opportunity here. Countries are at different points of the coronavirus curve. They have had different levels of exposure to epidemics in the past. They have complimentary resources of science, data, local experience and social experiments. Together our countries can benefit from fast, effective pooling of knowledge, coupled with mutual understanding of the context from which the information comes.

Not only that, but we’ve seen practical cross-border support brought between friendly neighbours, and there’s plenty more potential for that.

If we hit a second or third wave in 2020, or a worse epidemic in future years, the Irish who share a divided island, the Swedes and Finns, the Canadians and Americans may need to pool resources to get through peaks.

Rather than a source of competition, pride and superiority, the fact that countries are hitting their coronavirus peaks at different times may be an advantage.

International comparisons which are 10x more intercultural

These ten ways to make your international comparisons more intercultural, and more accurate, are built with the toolkit of the intercultural profession.

If your coronavirus work involves taking lessons from the experience of other countries, or giving epidemic guidance across cultural boundaries, consult an interculturalist and borrow some perspectives from the field of cross-cultural research.

More than ever, a clear-sighted view of other cultures could save lives in your own.